Decolonial Threads

My work is the result of archival research, a review of archaeological data, philosophical reflections, and cultural studies that enrich the works with important factors related to my personal history. In that regard, I am a multimedia artist because I work with different media. Still, something is always present in my artistic practice: the performance, which puts the “body” in a conscious state concerning other media. In a way that reflects my concerns and negotiations about body-political identity and being a woman, a woman who recognizes her Maya ancestral history and carries it into the space of contemporaneity through art.

I started working with textiles in 2008 when I made the clothing that I needed to film the video performance “Meditando el Error” (Meditating the Mistake). In the video, A man and a woman live together in an intimate space. The room is a colonial space. They walk tied up, in a rural area. They remain tied, they speak Maya Q’eq chi’ in a thought-out loud, and they try to move forward without getting anywhere. The clothing that both wear is based on the original textiles of the Verapaces in the north of Guatemala; Although the pieces were made mainly for the filming of the video, I later decided to create an independent textile piece and thus made the textile sculpture The killer (Aj Camsinel "Matador" 2009. My grandmother migrated from the village to the city, so these works talk about migration within the country and to the USA.

In 2011, I made several works that were part of a project entitled Cross Effects, for a solo exhibition in a Gallery in Guatemala. The traditional dyeing technique of yellow threads was the central element, conceptually and formally. Hence the “action of dyeing threads” and the “action of washing threads”.

Thus, in the video “Coloring the Threads”, the threads dyed with natural dyes in an intimate space, such as a kitchen, are reminiscent of the space in which women's daily lives are dyed. In the video “Discoloring the Threads”, on the other hand, I am decolorizing the strands in a river. The action shows us how close it is to nature, as we owe it to nature itself, but also that we feel the veins of the territory, as we realize that the rivers are the veins of the land.

“On the other side is the river and I cannot cross it;

On the other side is the sea, and I cannot cross it.”

Isabel Parra, in La Frontera.

That is, I accept the construction of the other (the subordinate woman) in colonial contexts because we have experienced a hostile context. I am an artist, designer, craftswoman, dyer, and philosopher, I am memory and present, tradition and modernity.

Therefore, these pieces can be viewed from the perspective of modernity/coloniality, in the sense of what sociologist Aníbal Quijano (1991) calls the "colonial world system”. With my work “Nudo Gordiano” (Gordian Knot: It is easier to cut it than to undo it), I dare to ask: How is the colonial history of our territories woven? Are we ready to cut these knots that bind the inequalities and the violence they generate, discrimination, racism, Eurocentrism, patriarchy, and extractivism? The invitation to untie or cut the knots is linked to liberation, i.e. we are invited to liberate ourselves, but the colonial impossibility will always exist.

In my artistic practice, some performances need a sculptural-textile work that is connected to the action, even if the works are independent of each other. For the performances Colorando las Hebras and Decolorando las Hebras, for example, there is a whole series of sculptural works that arise from these performances. The works have a common meaning, even if each one retains its specific concept.

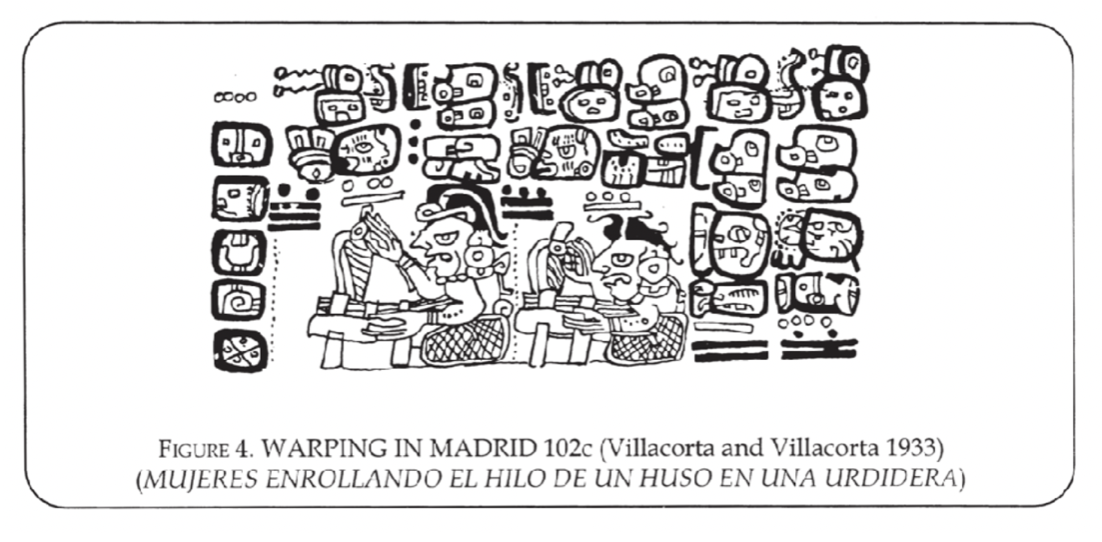

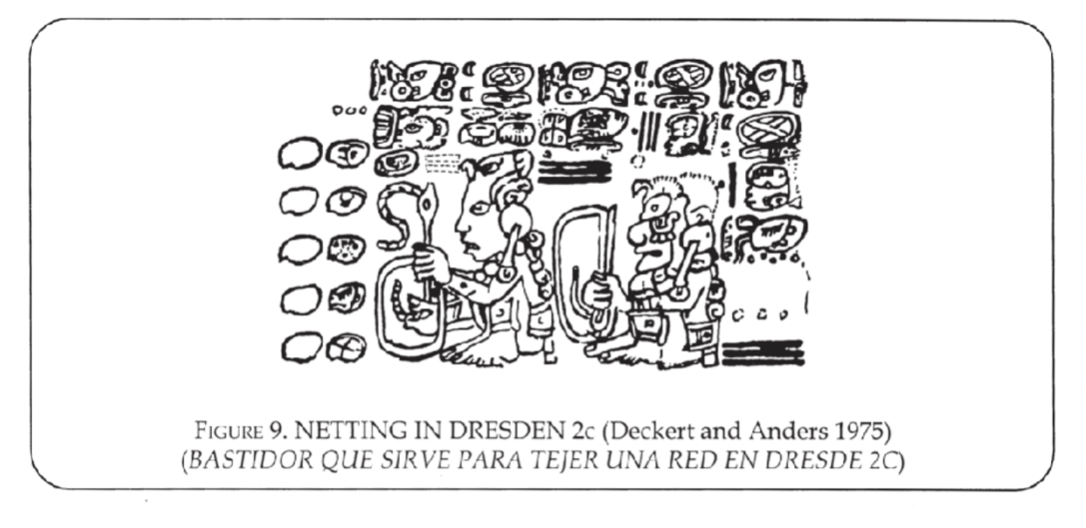

“On M102c two women are shown winding thread from a spindle onto a warping frame (Figure 4). The four legs of the frame are visible and extend through the horizontal bed to become pegs at the corners. In the first depiction, additional pegs at the sides are shown. The yarn can be seen passing several times around the pegs.” Ciaramella, (1999).

Regarding the series works Expoliada (2011) and the ongoing series (2011-2024), I have concerns about the overexploitation of natural resources, which leads the damage to flora, fauna, and water, is exposed. The sculptural works are not isolated from the body, because to build them, one must perform the “action of coloring, I mean dyeing”. The body is a collective body in that many people are involved in the creation, either because the spinning was done beforehand or because we dye the threads in my studio to create the desired tones and color palettes. But the body-artistic action is also a memory because it carries the ancient history of the old dyeing technique. The weaving process was paralyzed after it was organized, passing several times around the pegs and dyed. Then make the skeins of thread, which are the ones that hang in the installation.

“Spinal Column”, 2012 - 2017. It is a sculpture that, as a spine, shapes the lives of many Mayan women of Alta Verapaz, Guatemala. Weaves many stories, is an ancient monument, for example, the Quirigua stele with the mythical creation and calendar engraved in it. This contemporary monument or column is made with 87 skirt textiles made with foot looms by men, but is used by women in the present.

For our weaving ancestors, the action of dyeing and preparing the thread was closely related to the warp where the skeins were prepared. Examples such as the Bonampak mural demonstrate that the fabrics had color, they were dyed.

In the artwork “Offering for Chac” 2016 In a ritual associated with Chaac, the god of rain, I perform a ritual while dyeing the threads to thank for the water, with the fusion of three precious or medicinal elements: indigo, green, blue, and copal. The elements combined with the incense called copal promote Mayan blue, a turquoise color associated with water, an element typical of God and essential for life. Then with these dyed threads in blue, I create another Expoliada No3.2016. The concept has almost the same meaning as the yellow ones but with the performance as a ritual.

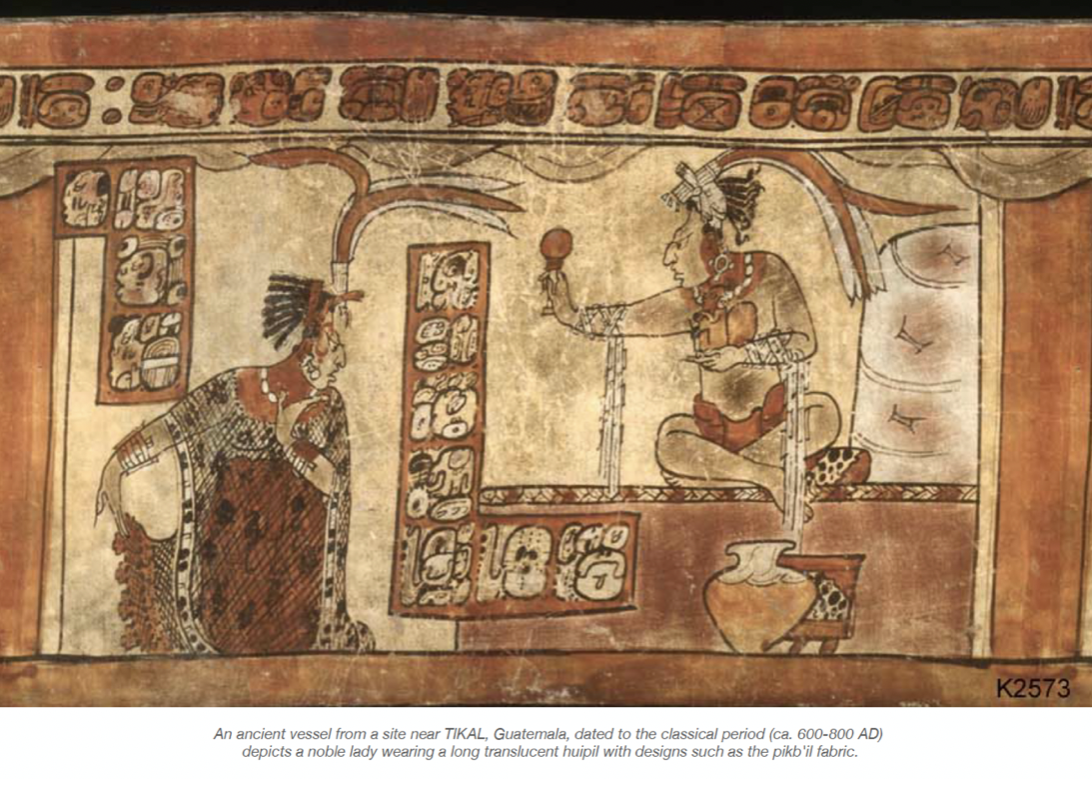

An ancient vessel from a site near TIKAL, Guatemala, dated to the classical period (ca. 600-800 AD) depicts a noble lady wearing a long translucent huipil with designs such as the pikb'il fabric.

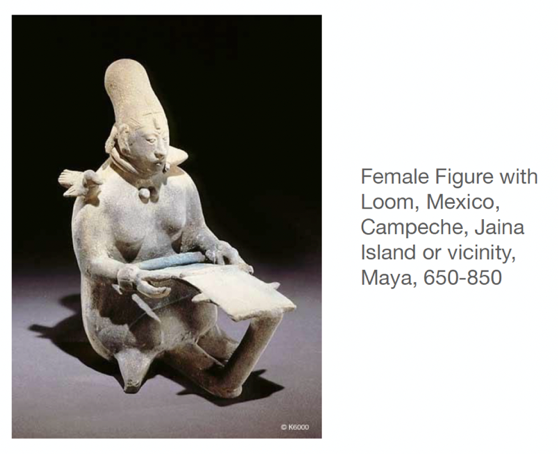

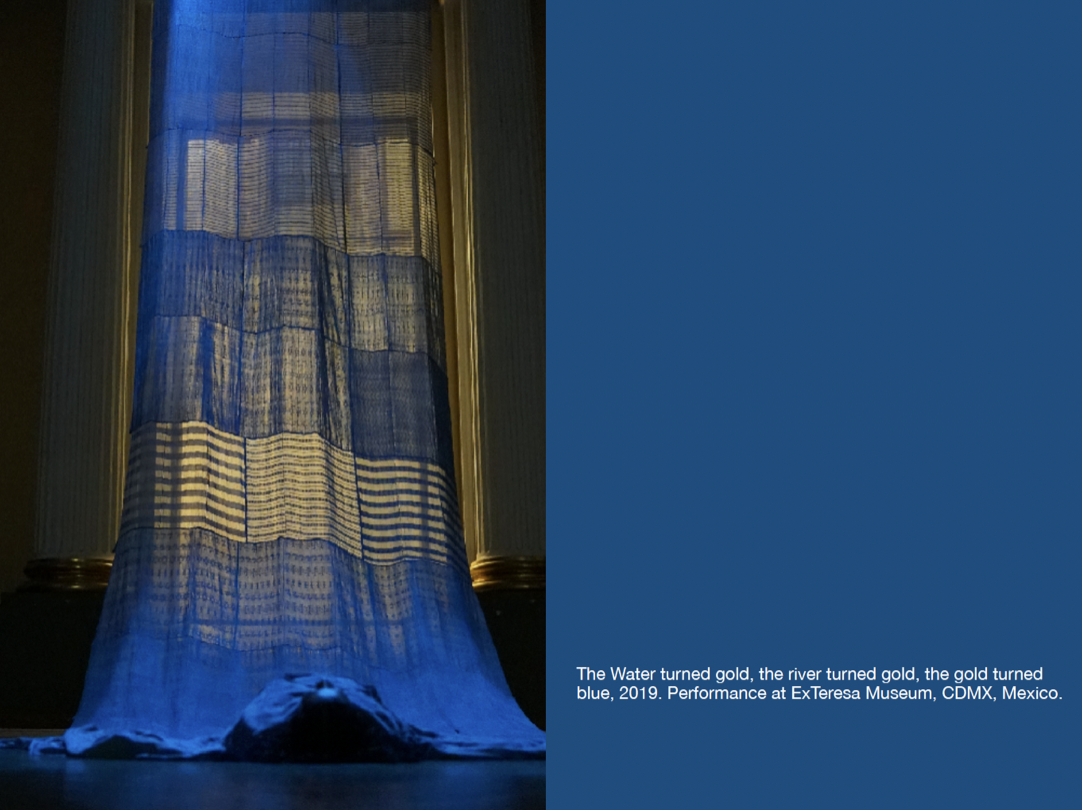

Like in the performance I made in 2019 “The Water turned gold, the river turned gold, the gold turned blue”. I have created a giant huipil installation made with 53 huipiles, woven on a backstrap loom, it is in the history of Mayan clothing, one of the oldest objects that have even resisted the passage of time. The Mayan goddess (symbolic image) of the Moon, the goddess Ixchel is a guardian and goddess of weaving, femininity, love, pregnancy, water, textile work, and medicine. She is seen in ceramic figures wearing a huipil or weaving a textile.

My maternal family is from the north of Guatemala, Alta Verapaz, where they weave and wear a huipil, almost transparent woven with white cotton thread. This type of brocade weaving is named pikb'il. The pikb’il hüipiles were dyed in my studio with indigo (indigofera guatemalensis), a pigment native to Mesoamerica with which Mayan blue has been obtained. Natural dyes also have healing properties so through my works of art I leave the invitation open to heal wounds: internal, ancestral, corporeal, spiritual, etc.

The textile that falls from the wall would be like a waterfall that covers the spirit of the water. During the performance, I am dressed with this giant textile breathing and performing an invocation to call the goddess Ixchel and the "muhel / spirit".

The intention of referring to water is because, in the last two years, a hydroelectric plant has dried up parts of the Cahabon River, one of the largest and mightiest rivers that cross northern Guatemala. All these extractive ways of seizing natural resources, in my opinion, are great wounds. The rivers, the lakes, and even the seas are wounded. But water is a sacred element for all the ancient cultures of America, from North to South for that, is one of the most precious resources for modernity-coloniality. The Mayan Q'echi', my relatives and ancestors, have a lot of respect for the spirit of the water, the hills and the mountains. This performance is an invocation to the spirit of water.

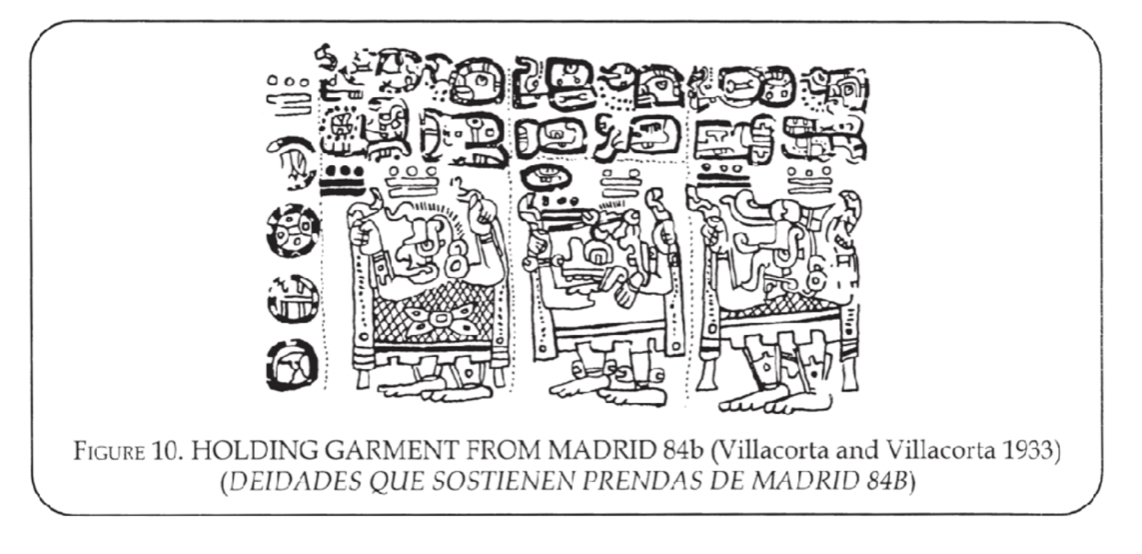

In M84b (Figure 10), three deities hold similarly shaped but differently decorated garments with crenelated hems and borders at the sides ending in ties. Barthel (1977:46) calls this a skirt-like textile or a cape. Y. Knorozov (1982:341-342) calls it a cloak. P. Anawalt (1981a: chart 15) classifies it as a xicolli or short jacket.

Portrait of Lady Six Heavens on Stela 24, standing over a K'inichkaab captive and dressed in corn goddess and moon goddess robes.

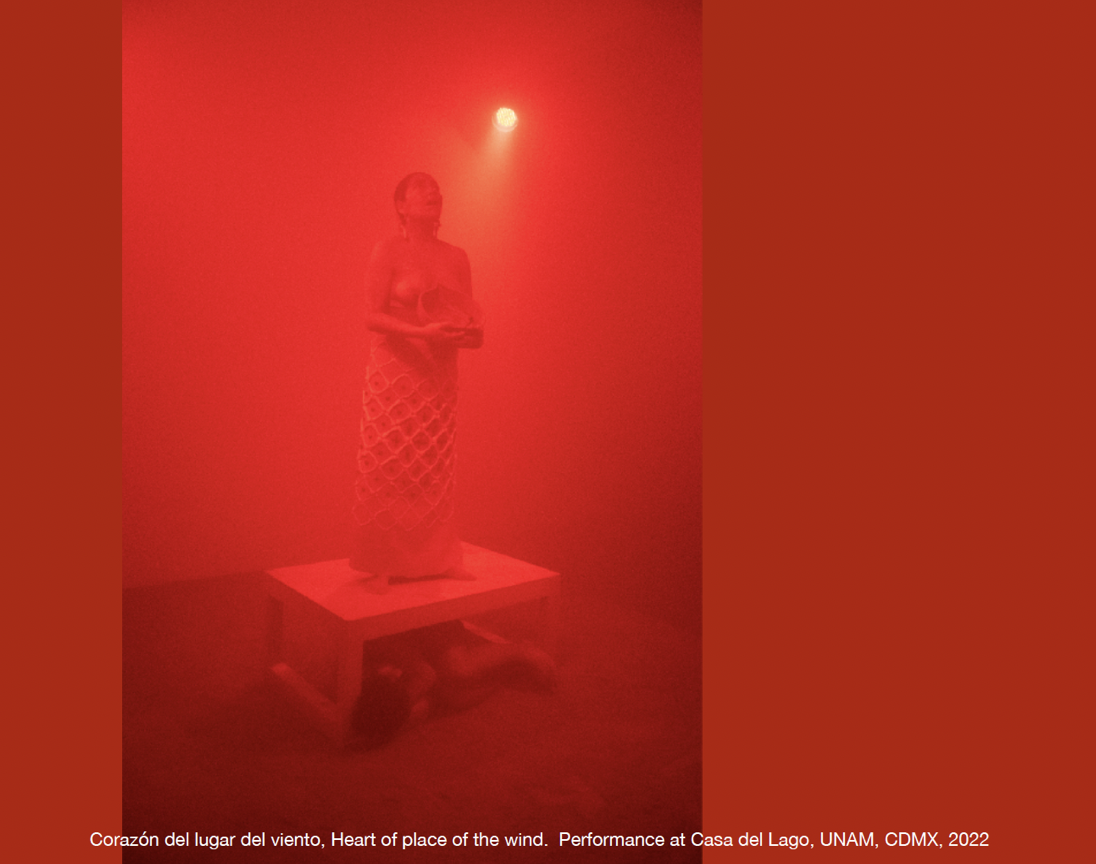

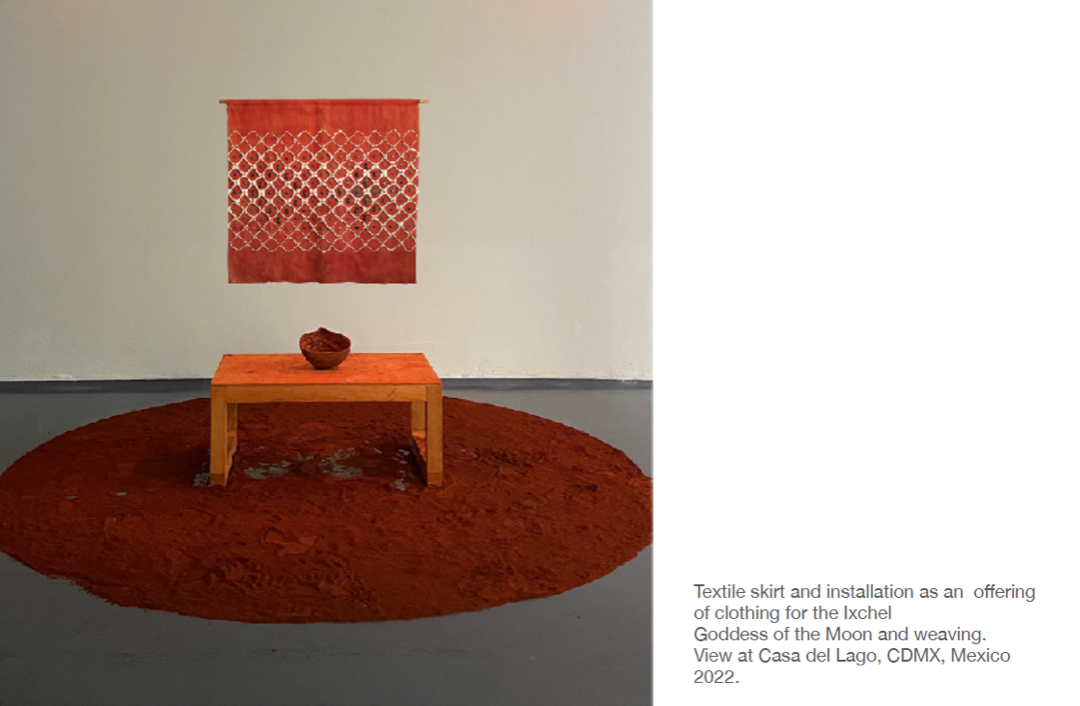

“Heart of the Place of the Wind” is a performance that I did in 2021. The entire performance is inspired by Mayan women archives who were rulers or queens in the pre-classic, classic Mayan period. The performance is a rite of tying stones and an offering of clothing. I am impersonating the moon goddess. I am making a personification of her as an empowered woman, the wind, and the rituality of the spirit. In the performance I am personifying the Mayan Women King: Wak Chanil Ajaw ( Señora Seis cielo ) Six Sky Women.

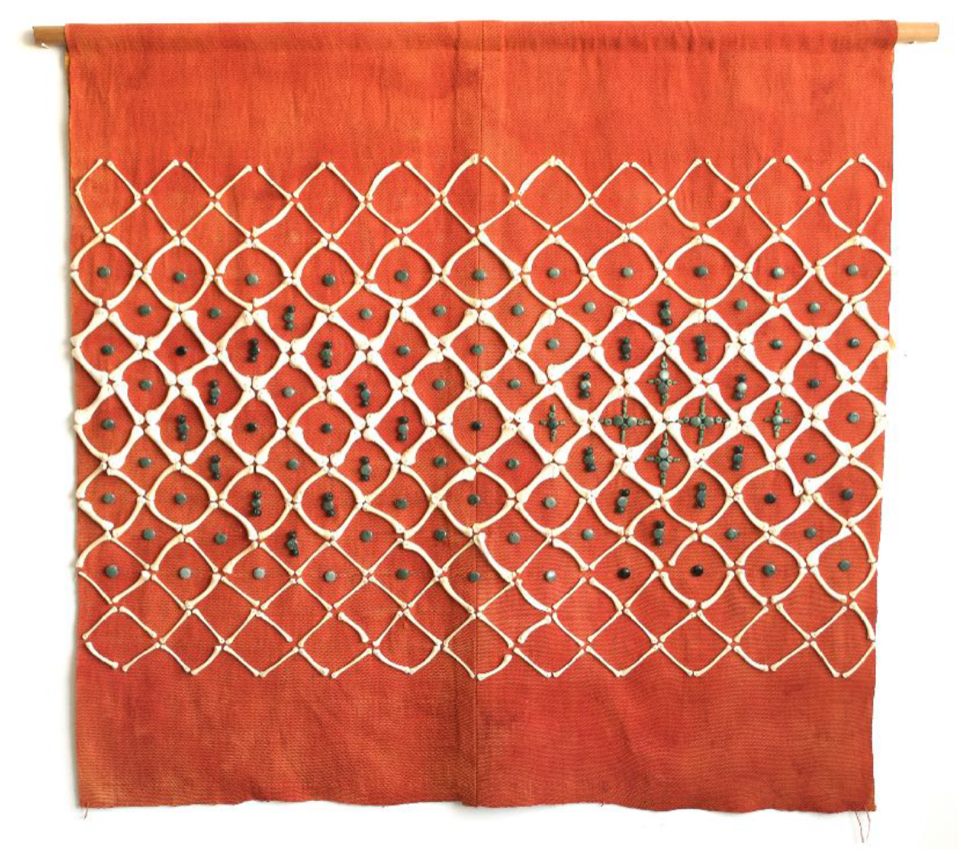

For this, I needed to create the skirt with which she seems dressed, that she appears on a Mayan stele found at the El Naranjo Archaeological Site. White textiles that were made on a backstrap loom by Mayan women from the B'atz Association from Tactic Alta Verapaz. The textile was brought into my studio, then we dyed the textile with achiote and turmeric. The skirt is embroidered with bird bones and jade stones from Guatemala. The bird bones were prepared in my studio with chicken wings for them to be white polished, varnished, and perforated. Then they were sewn like a skirt. I did all this process as an offering of clothing for the Ixchel Goddess of the Moon and weaving.

In such a way all these textile artworks that I have made are somehow decolonial threads, that confirm the works are created from a Mayan thought that promotes a modernity-coloniality detachment, perhaps linked to the transmodern utopian project of the Latin American liberation philosopher Enrique Dussel, so that we can transcend or move away as much as possible from the Eurocentric version of modernity.

Notes:

Ciaramella, Mary A.1999. Research Reports on Ancient Maya Writing 44:29-50. Center for Maya Research, Washington, D.C. https://www.mesoweb.com/bearc/cmr/RRAMW44s.pdf

Guirola, C. 2010. Tintes naturales, su uso en mesoamérica desde la época prehispánica. http://www.maya-archaeology.org/FLAAR_Reports_on_Mayan_archaeology_Iconography_publications_books_articles/12_tintes_naturales_maya_mesoamerica_etnobotanica_codice_artesania_prehispanico_colonial_tzutujil_mam.pdf

Lozano, L. 2021. Transmodernidad: método para un proyecto político decolonial. de enrique dussel a santiago castro-gómez. http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1692-88572020000300322#:~:text=La%20transmodernidad%20es%20un%20proyecto,las%20culturas%20universales%20%2Danal%C3%A9ctica%2D.

Quijano, A. 2014. Colonialidad del poder, eurocentrismo y América Latina. Buenos Aires: CLACSO https://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/clacso/se/20140507042402/eje3-8.pdf

Lopez, A. Un concepto de dios aplicable a la tradición maya. REVISTA BIMESTRAL Julio-agosto de 2018, vol. XXV, núm. 152

https://www.mesoweb.com/es/articulos/sub/AM152-2.pdf

https://www.mesoweb.com/es/gobernantes/naranjo/Senora_Seis_Cielo.html

For textual citations:

Monterroso, S. 2024. Decolonial Threads. Logan lecture series, Denver Museum.